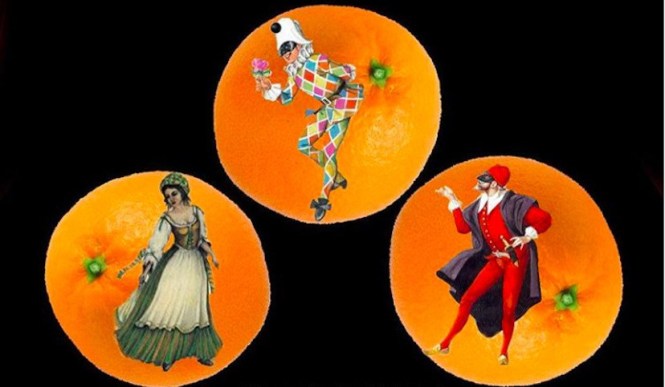

The whimsical score of the fairytale avant-garde opera “The Love to the Three Oranges” by Serge Prokofiev (composer and librettist) combines the elements of tragedy, comedy, fantasy and romance in the surrealistic staging. Based on the play by the Venetian Carlo Gozzi (1720-1806) “L’amore delle tre melarance”, “The Love to the Three Oranges” exhibits lavish Modernist theatrical techniques and commedia dell’arte which Prokofiev have possessed from the adaptation of Gozzi’s play by the provocative experimentalist of Russian drama theater[1] – the theater director, critic and whiter Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874-1940). Both the plot and the orchestration carry Prokofiev’s satire, charm and imagination which insensibly meet with the theatrical parody, vaudevillian buffoonery, and political and social irony.

The whimsical score of the fairytale avant-garde opera “The Love to the Three Oranges” by Serge Prokofiev (composer and librettist) combines the elements of tragedy, comedy, fantasy and romance in the surrealistic staging. Based on the play by the Venetian Carlo Gozzi (1720-1806) “L’amore delle tre melarance”, “The Love to the Three Oranges” exhibits lavish Modernist theatrical techniques and commedia dell’arte which Prokofiev have possessed from the adaptation of Gozzi’s play by the provocative experimentalist of Russian drama theater[1] – the theater director, critic and whiter Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874-1940). Both the plot and the orchestration carry Prokofiev’s satire, charm and imagination which insensibly meet with the theatrical parody, vaudevillian buffoonery, and political and social irony.

In 1918-1919, when Prokofiev worked on “The love to the three oranges”, his English skills were yet insufficient to write an elaborate libretto for the American commissioned opera; so, the best choice was to write the libretto in both French and Russian. Perhaps, the language barrier with the American audience also had played its role in the original failure of the production. Although Prokofiev did not intend to mock anyone in particular with the “The love to the three oranges” score, some of the initial critiques in the premiere in New York in February 1922 felt that “the work is intended, one learns, to poke fun. As far as I am able to discern, it pokes fun chiefly at those who paid money for it”[2]. Even though “The love to the three oranges” had an immense success in Europe and Soviet Union, the conservativeness of the American audience toward this Modernist opera had not changed until the revival of the “Three Oranges” in New York in 1949[3]. On the contrary to the American critic’s opinion, this opera in fact follows the tradition of Russian Kapustnik [cabbage skit], the traditional after-season capricious theatrical improvisations, parodies, and grotesque comedies, which usually were played in circus and cabaret styles, and brought up hot social topics of the local agenda[4].

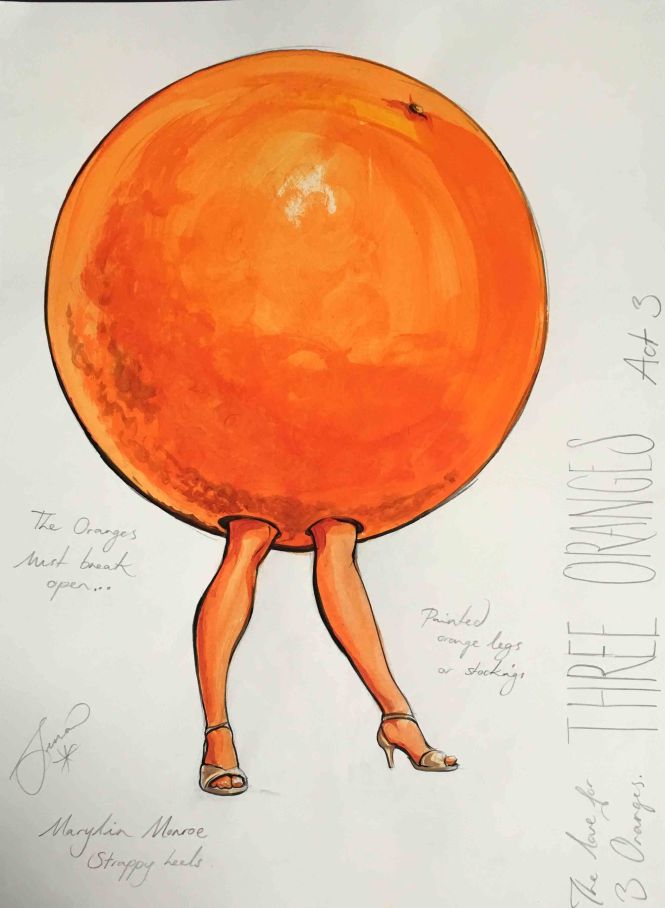

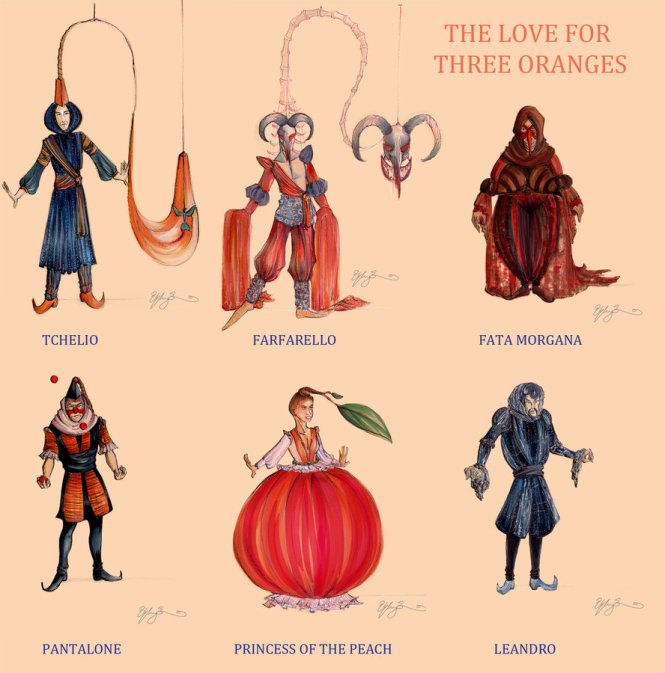

The surrealistic and anti-naturalistic plot of the prologue and four acts opera is intertwined and multilayered. Meyerhold in his play thought that the “slapstick comedy of masks is an antidote to the heavy melodrama and the petty naturalism”[5], and Prokofiev had followed the spirit fully in the “Three oranges”. Numerous characters are all dressed as playing cards: King of Clubs (bass), King of Spades – prime minister Leandro (baritone), jokers, malvinas (the oranges), etc. The special role is given to the Greek chorus: the chorus of five types of theater critics (Tragedians, Comedians, Lyricists, Eccentrics / advocates of Farce, and ten Ridicules / Cranks) who sit in elevated scaffolding around the stage and constantly argue about which genre of the drama is most favorable and how exactly the story should unfold. The confusing part of the plot is that the critics continually disrupt the action by commenting on the plot, therefore preventing any emotional involvement by the actual audience, and even get down to the stage to interfere with the action: in Act III, scene 3 the orange #3 Ninette (soprano) is opened by the prince in the desert, and is dying of thirst (the two previous oranges Linette (alto) and Nicolette (mezzo) are already dead from the thirst), so the Ridicules give a bucket of water to the Prince (tenor) to save her (the intention of the Ridicules is to enrage the advocates of Tragedy). In Act IV, scene 1, the “good” magician Tchelio (bass) (protects the Prince), and the “bad” witch Fata Morgana (soprano) (had cursed the Prince to love the three oranges, and had turned Ninette into a giant rat) accuse each other of cheating; here the Ridicules again take a ride to the stage to lock her up, so Tchelio can restore Ninette to her original form and let her marry the Prince. There’s also an opposite interference with the ‘critics’ by the characters: in Act II, scene 1 King of Club’s scheming niece Clarice (alto), her protector King of Spades/prime minister Leandro, and Brighella (Leandro and Clarice’s dimwitted minion) discuss their respective preference in theatre: tragedy, comedy, and commedia dell’arte.

Makiko Hirata mentions that “Prokofiev was a descendant of Russian composers who sought to establish their own unique voice, independent from the European influence. One of the ways in which they attempted this was by looking to the Orient”[6]. The ambiguous harmonies (the most famous quirky and grotesque March pierces through the entire score, accompanying duets, sounding in orchestral intermissions, as in Act II ending of scene 1), chromaticism (Fata Morgana’s part, demons), pictorialism in orchestral parts (repetitive orchestral Scherzo in the closing of Act III scene 2), modal melodies in the arias (Act III, scene 3 Ninette’s aria “Moi, je m’appelle Ninette”) all indicate a certain level of Orientalism in the opera. The minimalist pattern runs through the entire score: for instance, in Act II, scene II when Fata Morgana is knocked down by jester Truffaldino (tenor) and exposes her underwear, the terminally hypochondriac Prince starts laughing with the opening motif of Beethoven’s 5th symphony E-E-E-C, while accompanying violins repeat the motif E-E-E-F#-G-A continuously for the duration of 48 measures. The musical ideas are actually inspired not only by Mozart and Lorenzo da Ponte collaboration, and the Orientalist “Magic Flute” and “Abduction from Seraglio”, but also by Meyerhold who referred to the Dionysian cult as a prime engine for “The love to the three oranges”: “the ritual dedicated to the god of wine has pre-established meters and rhythms, and certain prescribed methods of movement and gesture”[7]. Regardless of the multiple humorous references to the works of other composers, Prokofiev’s most successful operatic canvas remains fresh and original, fueled by effortless playfulness of the musical language.

Bibliography

- Hirata, Makiko. Orientalism in Love for Three Oranges. Retrieved from: http://www.academia.edu/10555872/Makiko_Hirata_Orientalism_in_Love_for_Three_Oranges.

- Hoover, Marjorie L. A Mejerxol’d Method? Love for Three Oranges (1914-1916). The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring, 1969), pp. 23-41.

- Mitchell, Donald. Prokofieff’s “Three Oranges”: A Note on Its Musical-Dramatic Organization. Tempo, New Series, No. 41 (Autumn, 1956), pp. 20-25.

- Pisani, Michael V. A Kapustnik in the American Opera House: Modernism and Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges. Oxford University Press: The Musical Quarterly, 81, No. 4 (Winter, 1997), pp. 487-515.

- Prokofiev, Serge. “L’Amour de trois Oranges: Opera en 4 actes et 10 tableaux avec Prologue”. Livret et musique de Serge Prokofiev (d’apres Carlo Gozzi), op.33. Reduction pour chant et piano par l’auteur. Leipzig: Breitkopf&Hartel, 1922.

- Robinson, Harlow. Love for Three Operas: The Collaboration of Vsevolod Meyerhold and Sergei Prokofiev. The Russian Review, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Jul., 1986), pp. 287-304.

- The Love for Three Oranges: A Slaphappy Fairy Tale Makes a Smash-Hit Opera. Life, 2 October 1950.

[1] Harlow Robinson. “Love for Three Operas: The Collaboration of Vsevolod Meyerhold and Sergei Prokofiev”. The Russian Review, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Jul., 1986), pp. 287-304.

[2] Michael V. Pisani. “A Kapustnik in the American Opera House: Modernism and Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges “, in The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 81 no. 4 (1997), p. 490.

[3] The Love for Three Oranges: A Slaphappy Fairy Tale Makes a Smash-Hit Opera”, Life, 2 October 1950.

[4] Pisani, p. 487.

[5] Makiko Hirata. Orientalism in Love for Three Oranges, p. 2.

[6] Hirata, p. 6.

[7] Marjorie L. Hoover. A Mejerxol’d Method? Love for Three Oranges (1914-1916). The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring, 1969), p. 28.

Written for Mills College

December 2018